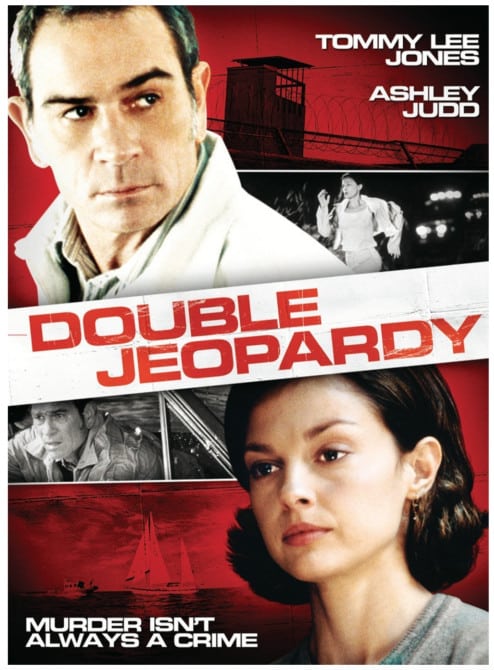

In 1999, a Hollywood movie called “Double Jeopardy” came out.

The film begins with a woman waking up at sea on her family’s yacht in a storm. When the Coast Guard arrives, she has blood all over her, a knife in her hand, and her husband, who had been the only person onboard the yacht with her, is missing. The husband’s body is never found. The wife is eventually arrested, tried, and convicted for her husband’s murder.

While the wife is serving time in prison, she begins to suspect that her husband faked his own murder and framed her in a scheme to get rich. Another inmate tells the wife that because she has already been convicted of her husband’s murder, that under the 5th Amendment’s double jeopardy clause, she can now kill her husband for real and not face criminal prosecution. Though it’s never a good idea to take legal advice from a prison inmate, the wife believes she can now legally kill her husband. When the wife gets paroled, she starts looking for her husband. When she finds him alive and well, she points a gun at him and says: “I learned a few things in prison. I could shoot you in the middle of mardi gras and they can’t touch me.”

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Double Jeopardy is defined as the act of causing a person to be put on trial two times for the same crime.

The protection against double jeopardy can be found in the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which states that no person shall “be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb.” The Florida Constitution also has a double jeopardy protection as part of Florida’s Declaration of Rights, which states, “No person shall…be twice put in jeopardy for the same offense.”

In 1957, in a case called Green v. United States, the United States Supreme Court explained the rationale for the double jeopardy clause, stating that:

The constitutional prohibition against “double jeopardy” was designed to protect an individual from being subjected to the hazards of trial and possible conviction more than once for an alleged offense…. The underlying idea, one that is deeply ingrained in at least the Anglo-American system of jurisprudence, is that the State with all its resources and power should not be allowed to make repeated attempts to convict an individual for an alleged offense, thereby subjecting him to embarrassment, expense and ordeal and compelling him to live in a continuing state of anxiety and insecurity, as well as enhancing the possibility that even though innocent he may be found guilty.

The double jeopardy protection does not apply until jeopardy has “attached.” With a jury trial, jeopardy attaches when a jury has been selected and sworn (taken an oath). With a bench trial (a trial in which a judge decides the case rather than a jury), jeopardy attaches when the first witness has been sworn.

It’s important to remember that there are times when the government can try a defendant more than once for the same offense. For example, if a defendant goes to trial, is convicted, but then gets the verdict overturned on appeal, the double jeopardy clause normally does not prevent the government from retrying the defendant. That’s what happened in the famous case of Miranda v. Arizona. In that case, Mr. Miranda was convicted for the kidnapping and rape of an eighteen-year-old woman, but because police had not informed Mr. Miranda of his rights to obtain an attorney and remain silent during his custodial interrogation, the United States Supreme Court overturned his conviction. Because the double jeopardy clause did not prevent the State of Arizona from retrying Mr. Miranda, the prosecutor filed the charges again. At the second trial, the prosecutor was not allowed to present evidence from Mr. Miranda’s confession. However, the victim was able to testify against Mr. Miranda, the jury found him guilty, and the judge sentenced him to prison.

With respect to the “Double Jeopardy” movie, the wife’s problem is this. When a grand jury or prosecutor accuses a person of murder, they charge that the murder took place at a particular location and time, and double jeopardy applies only to the murder that took place at that particular location and time. So, if the wife in “Double Jeopardy” were to kill her husband at a different location and time, then double jeopardy would not apply. Therefore, the inmate that told the wife that if she found her husband alive, that she could kill him with impunity, was wrong.

As far as what happened to the husband and wife in “Double Jeopardy”, the wife does eventually shoot and kill the husband in a shoot out. However, it would have been the law of self-defense, rather than the law of double jeopardy, that would have determined whether or not she would have been convicted of murder.

Discover the intricacies of Florida’s Self-Defense Legislation, including an in-depth look at the state’s Stand Your Ground Law.

Posted in Criminal Procedure